Rewilding Underground Ecosystems

Ecosystem Recovery in the Magdalena River Valley in Colombia

Rewilding Underground Ecosystems in the Magdalena River Valley in Colombia. Working to conserve and regenerate the last forest relics in a deforested area under pressure by land use change: cattle ranching, mining and oil drilling.

enlace al artículo

- Rewilding is the process of rebuilding a natural ecosystem after human disturbance

- Fungal rewilding is an important, but largely ignored, component of ecosystem restoration

- SPUN is tracking the recovery of underground fungal systems following cattle ranching abandonment to test if ecosystems can be fully restored to diversity found in adjacent intact forests

- Led by Dr. Adriana Corrales, SPUN will follow rewilding processes both above and belowground across a 20-year period

- The goal is to develop low-cost, easy methods and protocols for leveraging mycorrhizal fungi to restore degraded tropical ecosystems

Dr. Adriana Corrales has initiated a 20-year project in Colombia's Magdalena River Valley to monitor how mycorrhizal fungi contribute to the recovery of a biodiversity hotspot degraded by intensive logging and cattle ranching. In this article she describes her investigation: whether ‘passive rewilding’–allowing damaged ecosystems adjacent to healthy, intact forests to regenerate without intervention–will offer a solution to restoring degraded ecosystems across the tropics.

Tropical Rewilding: Restoration and Ecosystem Functionality

What is rewilding and how can it help us recover ecosystem processes? This is currently a major question in global restoration. An estimated 30% of the planet’s soils are moderately to highly degraded. Can rewilding be used to fully recover above and belowground biodiversity losses following cattle ranching, mining and other types of land use changes? Can this be achieved passively or do specific actions need to be taken?

Rewilding is the process of rebuilding a natural ecosystem after human disturbance. It focuses on restoring processes and food webs to create a resilient ecosystem (Carver et al., 2021.) Rewilding attempts to return the ecosystem to its original trophic structure and previous processes, even if species composition has changed in the meantime.

While rewilding is a promising restoration strategy, we currently lack data on when and where it is most successful. Measurement and monitoring of ecosystem rewilding is a challenge, especially for underexplored tropical regions lacking baseline diversity data on plant, animal and fungal communities. Additionally, we are dealing with a moving target in terms of restoration, as new conditions and challenges emerge with ongoing global change such as temperature, pollutants, nutrient levels, invasive species, etc.

Our aim is to design and implement a passive rewilding project in the Magdalena Valley with a focus on monitoring above and belowground biodiversity. Our central question is: what happens to plant and mycorrhizal fungal diversity following the abandonment of cattle farming? Our experiment design includes plots where: (a) cattle farming has been recently abandoned, (b) secondary forest is regenerating, (c) primary forest is protected and monitored as a benchmark for healthy, intact forests.

Why Tropical Fungal Rewilding?

Tropical underground ecosystems contain some of the most diverse fungal communities on Earth. However, the role of mycorrhizal fungi in restoration has not been well-documented in the tropics.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Can soils that house high levels of biodiversity be restored? If this diversity is lost via ranching, mining or other forms of land-use change, can the original fungal communities ever be recovered? If the same fungal species fail to be restored, can their overall functions still be recovered?

STUDY SITE

Our study area is in the Magdalena-Urabá ecoregion, part of the Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena biodiversity hotspot (formerly called the Chocó-Darién-Western Ecuador Hotspot). It is a highly diverse region, with many endemic species. In the drier soils, the flora is dominated by tropical lowland forest. In the permanently or temporarily flooded soils, the ecosystems house palmettos and wetland vegetation. This inter-Andean valley is surrounded by tall mountains. It is biogeographically isolated from surrounding lowland forests, making it an ideal study site for rewilding.

LOCATION BACKGROUND

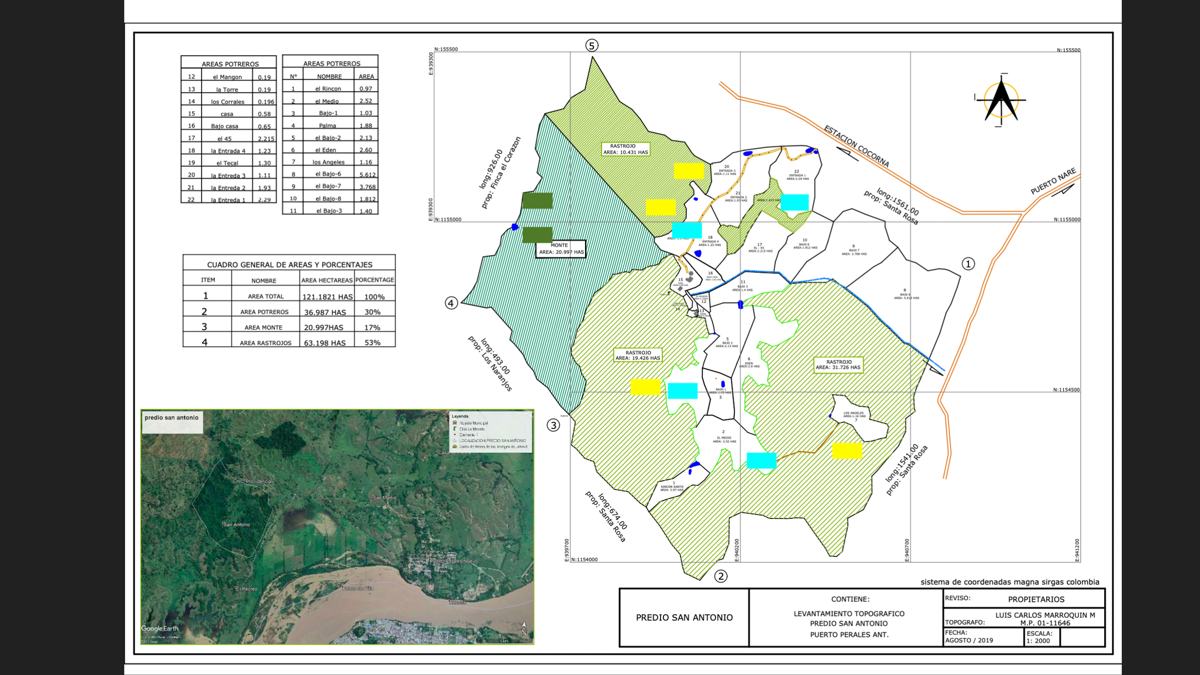

Our experiment is taking place on private property. The area is ~120 hectares; roughly equivalent to a 1-kilometer square pixel. This is the same scale we use for our predictive biodiversity mapping. Damage in the study area was caused by extensive logging of primary forest. Subsequent draining of the pre-existing wetlands completely altered the water flow in the soil and the habitat for many species. The introduction of exotic species has also had significant negative impact. After initial logging roughly 80 years ago, cattle ranching began. As cattle were introduced, there was large scale treatment with herbicides and exotic pastures grown specifically for the cattle.

Establishing Research Plots, Tagging Trees, and Measuring Biodiversity

To monitor changes over time, we are establishing so-called “permanent plots.” These plots are established by scientists, who carefully identify plant, animal, and now fungal species, allowing researchers to track changes over time. We established plots measuring half a hectare (5,000 m²) spanning three ecosystem types: (1) primary forest (theoretically untouched), (2) secondary forest (abandoned 10-30 years ago) and (3) recently abandoned cattle pasture. These three ecosystem types can be thought of as a ‘chronosequence’, with the recently abandoned pasture plots as ‘time zero’. To identify statistical trends, we need replication. Therefore, we established replicate plots for each of the ecosystem types. Specifically, we established four replicates per ecosystem type. Unfortunately, we were only able to establish two replicate plots in the primary forest because so much of this ecosystem has already been destroyed. In total, we have 10 half-hectare plots.

Next, we needed to establish what communities are in each of the 10 plots. It is a massive job– especially in the primary forest–to identify, measure, and map all the trees in the plot area. This means tagging, collecting, and identifying all species. We worked with the Botanical Garden of Medellín to help establish these plots because they are the world experts in identifying the plant species of the Magdalena Medio ecoregion. It took approximately two weeks to set up each plot, and the entire process spanned four months. We did not tag every tree; only those greater than 10 centimeters in diameter were included. Even within just half a hectare, this sometimes meant tagging more than 100 trees. In plots undergoing regeneration, we tagged trees with diameters greater than 5 centimeters. With support from the Botanical Garden of Medellín, we are now creating botanical vouchers for all species. This team has been an ideal complement to SPUN’s expertise in belowground ecology.

To date, we have identified a huge number of different plants across the plots. The current count is over ~140 plant species across all the plots. We have also identified one endangered (EN) and two vulnerable (VU) plant species: Zamia incognita (EN), a small species of cycad in the Zamiaceae family and endemic to Colombia, and Ephedranthus columbianus (VU) and Vitex columbiensis (VU) both also endemic of Colombia. We expect to find many other endemic plant species (and potentially endemic fungal species) because this region is very geographically isolated. This means genetic flow is limited, driving the evolution of unique traits.

In addition to plant species, we have recorded over 100 species of birds, and many mammals and recently discovered the return of capybaras to the area. We also identified the white-footed tamarin (Saguinus leucopus), an endangered monkey, endemic to the area.

Plot type classifications: [on the map] Primary forest (green), secondary forest (yellow), pastures recently abandoned (teal). The plots are not geometrical because of the pre-existing land-use shapes.

Gathering Baselines for Soil Health and Fungal Species Composition

While many restoration projects track plants and animals, very few monitor fungi. In fact, the vast majority of restoration projects fail to track any underground variables. This is very problematic because soil health and fungal communities are very important for restoration success.

Our first step is to establish a baseline for soil health and fungal composition. We do this by collecting soil samples to characterize the fertility and diversity across the three types of plots. We collect data on abiotic conditions (pH, nutrients, carbon), and DNA of the fungal communities. This is crucial because we need to document all temporal changes in species composition. This allows us to test if fungal species composition is associated with changes in plant composition and ecosystem properties, like carbon storage.

When we take soil samples, we sequence the fungal DNA to determine which fungal communities are present. You can read about our sampling protocols here. We're working to sample the top 10-15 cm of soils. We will also sample deep soils, up to a meter in depth, in the center of the valley. We are interested in identifying potential ‘keystone’ mycorrhizal species that are consistently associated with successful plant community restoration, as well as mycorrhizal fungi that are associated with improvement of ecosystem services such as increased carbon storage, improved water cycles, and tighter nutrient cycles.

Invasive Species

An additional challenge is the encroachment of invasive species, especially in the secondary and recently abandoned pasture ecosystems. The invasive species oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) is of particular threat, and we worry that with passive rewilding, these palms could dominate the whole area. This is additionally complicated because the parrots and macaws (Ara ararauna, Ara severus, Pionus menstruus, Amazona amazonica, and Amazona ochrocephala) love eating palm fruit and disperse it widely. This leads to a moral dilemma. The oil palm is an important food for these iconic birds and eliminating their food source will have repercussions.

Our past work on coconut palm suggests that the mycorrhizal fungi associated with palms are very different from those of old-growth rain forest trees (read about our Palmyra work). If these invasive oil palms are changing the fungal communities belowground, we need to develop methods to introduce native plants alongside their native fungi.

Tracking Ecosystem Rewilding: A Twenty-Year Plan

We plan to monitor these plots for the coming 20 years, ideally collecting data at least 10 times across each plot. This timeline depends on funding. More funding means more intensive sampling and higher resolution fungal datasets.

Alongside plant, animal and fungal biodiversity, we want to collect data on ecosystem changes. This includes measuring variables such as aboveground biomass and water flow regulation. Documenting ecosystem services is central to the project. Carbon storage is important because primary forest productivity can be very high if properly restored. We are interested in understanding the relationship between biodiversity and carbon storage. The natural wetlands potentially have deep soils, but we don’t know how much carbon can be stored over time in these wetlands. Water regulation is likewise important. What will happen when we allow inundation or flooding in the area once again?

What We Hope to Learn by Monitoring a Tropical Rewilding Project

There is an urgent need to develop low-cost, easy methods and protocols for leveraging soil fungi to restore degraded ecosystems. Passive rewilding is one method gaining attention. However, passive rewilding processes have not been carefully studied in the tropics. As a result, we don’t yet understand recovery timelines, or whether ecosystem functions and/or species compositions are successfully restored. These processes have never been studied underground, so we need long-term monitoring of underground community recovery.

The dream is to turn this location into a biological station. We want it to be preserved so that people can come to Colombia to conduct ecosystem research of all types. We currently have a Colombian PhD candidate from UCLA studying these plots to understand how climate change affects the physiology of tropical plant species. If we can establish a tropical field station for studying the relationships between mycorrhizal fungi and ecosystem recovery, we will be able to provide data, protocols and underground monitoring tools to a new generation of restoration scientists who want to better leverage fungi to restore degraded habitats around the world.

…To Be Continued

This is obviously a very exciting research project on many levels. Not the least of which is that it’s an unfolding story. Sign up for our Newsletter to get regular updates. We also plan to post again after the next round of sampling.