Underground Astronaut

This article by Jinsu Elhance explores underground complexity, microbial mapping methods and his journey to becoming an Underground Astronaut.

enlace al artículo

- Remote sensing imagery of Earth's surface can be used to predict diversity, health, disturbance or endemism of underground microbial communities.

- Aboveground (remote sensing) observations are combined with mycorrhizal fungal DNA data.

- Breakthrough science reveals new aspects of underground networks, for example that carbon can flow in 2 directions at once.

- There is potential for mycorrhizal fungi to underpin new ways of resource management in Kenya's rapidly degrading grasslands or mangrove ecosystems.

- Restoration, ecosystem health, food production, and climate regulation are just a few of the services provided by mycorrhizal fungi.

What is an Underground Astronaut anyway? Similar to cutting-edge exploration in space and deep oceans, new frontiers are being discovered under our feet. Led by a group of researchers known as “Underground Astronauts,” new patterns are being discovered in underground ecosystems. Like astronauts that explore space, Underground Astronauts employ emerging techniques to make invisible worlds become visible, including high-resolution imaging, sequencing of unknown organisms, and monitoring changes belowground. This exploration led to the 2025 launch of the Underground Atlas – a high-resolution mycorrhizal biodiversity mapping tool.

This article by Jinsu Elhance explores underground complexity, microbial mapping methods and his journey to becoming an Underground Astronaut.

The astronaut component is…sort of spacewalking down to the microscopic level… underneath the soil.

What is an Underground Astronaut?

An underground astronaut is somebody who is curious about the complexity of Earth's underground ecosystems and wants to surface those answers, to push the rest of humanity to feel more deeply connected with the systems that underpin life.

I considered myself an Underground Astronaut after taking my first soil core. That was when I made the shift from being an aboveground observation-based scientist to one studying underground systems. As I started digging soil samples, I began to imagine how molecular data collected in the field can transform our understanding as we zoom out from the genetic to the planetary.

Spacewalk: connecting satellite imagery to underground eDNA

Before joining SPUN, I worked as a geospatial data scientist mapping forests and aboveground ecosystems. I worked with Earth observation imagery taken from satellites, looking at things like tree cover and the diversity of mangroves.

It has been an interesting expansion of scale and transformation, to get into the field, breaking into the underground to collect soil cores, and processing that material for eDNA. In connecting these data to satellite imagery, we are spanning from the microscopic to the global scale. This work feels like we are connecting the earth and the sky.

My definition of Underground Astronaut includes a focus on underground ecosystems and the diversity and complexity of soil dynamics. In particular, the goal is to focus on how microbes like fungi and bacteria, and complex root systems and micro-topographies of the underground, all contribute to construct the base of the pyramid of life on Earth.

Once you understand and appreciate that complexity, you want to explore: step in and start to unravel the infinite number of questions that come from being curious. That curiosity is another astronaut component. It is a sort of spacewalking down to the microscopic level underneath the soil and seeing what's possible underground.

The Earth as a blue marble

When I think of the term astronaut, I remember the iconic photo of Earth as a small blue dot, and how much that image did for igniting the curiosity of the general public. It was one simple image but it sparked a global sentiment that we are collectively responsible for the health and well-being of the only place that we know for certain in the universe that has life. There is a fragility in that photo, which can also be found in the microscopic photos that we've taken of nutrient flows through mycorrhizal networks. And although not on the same scale, our recent images have done something similar in quickly bringing people to an awareness that the systems that underlie life on earth warrant our concern and attention.

Mycorrhizal fungi are the vital bridge between the belowground and aboveground kingdoms

Earth’s mycorrhizal systems rely on very intricate processes of nutrient transfer. These are processes which are not passive. Fungi have specifically evolved to facilitate movement of nutrients through soil. We're showing people what this looks like for the first time.

There are very few papers using remote sensing imagery of the planet's surface to infer about diversity, health, disturbance or endemism of underground microbial communities. You might assume that little is possible there because light doesn’t penetrate the soil. But mycorrhizal fungi are an interesting way to break that perception, because mycorrhizal fungi are so connected to their aboveground partners. An estimated 80 percent of plant species partner with mycorrhizal fungi.

We know that health and diversity in mycorrhizal networks affects plants' ability to uptake nutrients, resist disease, and colonize even desert landscapes.

Predicting belowground diversity with aboveground imagery

The Underground Atlas uses remote sensing imagery to predict belowground community diversity based on aboveground observations.

Aboveground, we're looking at environmental covariates, using globally gridded datasets of soil moisture, climate variables, eco-regions and plant productivity, which we're correlating with our mycorrhizal soil samples. We combine aboveground (remote sensing) observations with mycorrhizal fungal DNA data. The result is a chance look at plant trait characteristics to see how they change across the landscape. The combination of remote sensing and our field observations of mycorrhizae helps us identify and understand patterns.

Increasing predictive certainty

One important part of our work is identifying places where predictive certainty is less than what we want. We face uncertainty when we don't have quality information (in this case soil samples) about a place, meaning the quality of the conclusions and the statements that we can make about diversity and mycorrhizae in those places is limited. Places lacking data tend to be in ecosystems that are difficult to access, often geographies in the Global South.

However, as more and more people get involved, the spread of our sampling distribution is rapidly increasing. Our latest program is creating a global network of researchers to translate science into legal and governance action and impact.

Expeditions to the American Southwest and Alaska

I recently participated in two expeditions across vastly different ecosystems, both of which focused on identifying under-explored places to collect data. The first one was to arid and semi-arid ecosystems in the American southwest, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas.

We collected some of the first mycorrhizal soil samples in these ecosystems. We'll feed the data back into our global predictive models, which will help us predict mycorrhizal diversity with greater certainty in both of these specific ecosystems, and in similar ecosystems around the world. The sampling gap extends beyond the American Southwest to arid ecosystems worldwide that have historically been under-sampled.

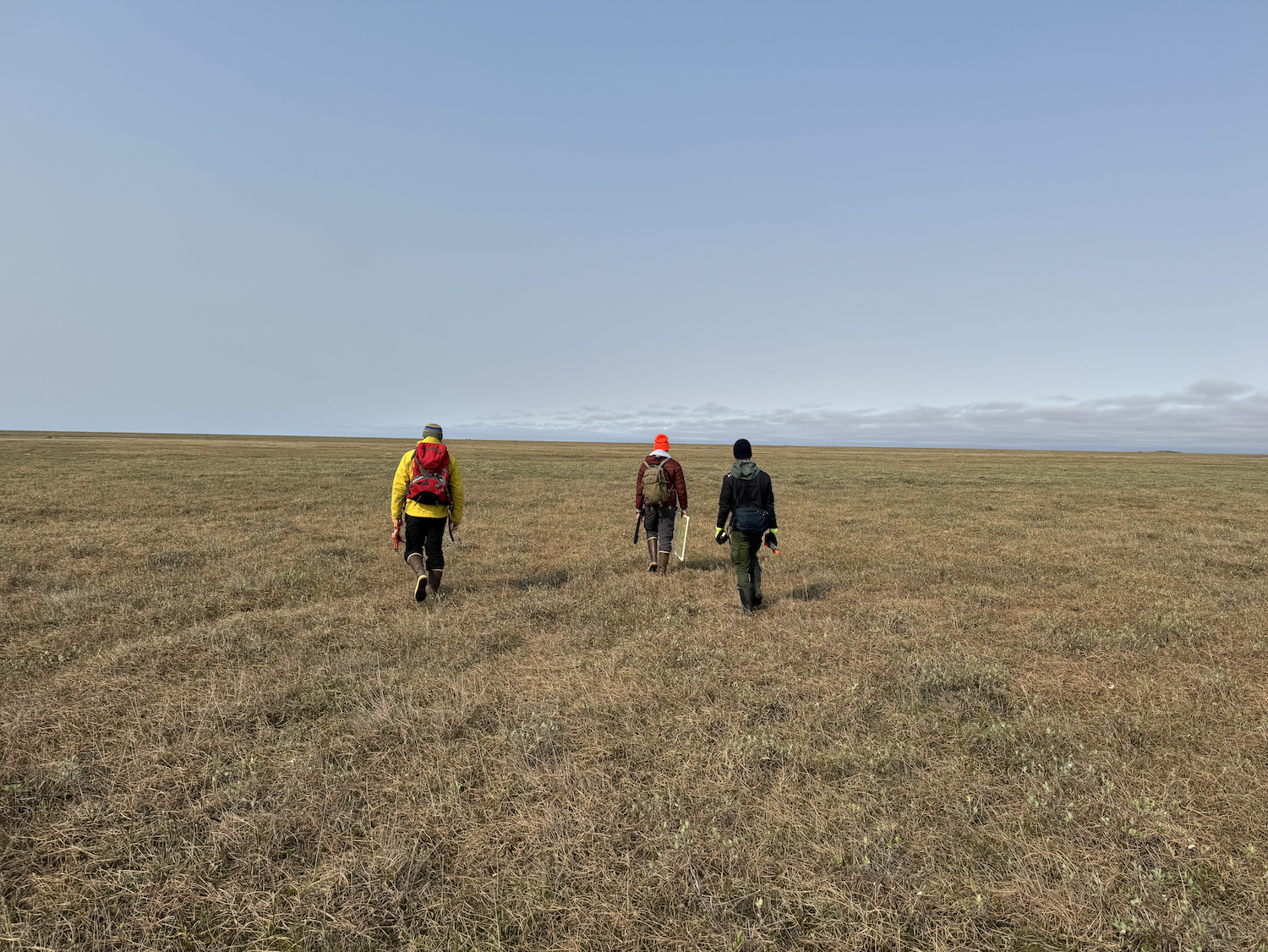

Our second expedition brought us to the Arctic tundra where we sampled near Deadhorse, Alaska, against the Beaufort Sea, to understand how mycorrhizal communities are changing in thawing tundra ecosystems.

We want to fill in the gaps, the missing puzzle pieces in the comprehensive picture of mycorrhizal diversity around the world. And there are many missing puzzle pieces. Optimistically, we now have a fantastic network of Underground Explorers and Associates and are creating a massive amount of data for the benefit of the conservation of mycorrhizal fungi.

Fungi and climate regulation

Why is all this so important? Because mycorrhizal fungi take care of the plants that feed us, give us clean air, and stabilize our soils. We are learning that fungi play a significant role in regulating our climate. By observing them and trying to figure out what specific environmental and ecological niche these fungi need in order to stay healthy, we can try to protect them.

I would love to provide a timeline of urgency for the conservation of mycorrhizal fungi, but we're still trying to get a sense of the parameters. We know that the climate is changing rapidly and that the speed of our monitoring capabilities for mycorrhizal fungi have not yet caught up with the rate of impact and destruction. These impacts include extreme weather events, soils degrading globally, and land converted for agricultural use and development. All of this is constantly happening, as cement is being laid over soil, destroying mycorrhizal communities in ways we understand but can't yet quantify. So the urgency lies in making mycorrhizal fungi a consideration in the minds of both policymakers and the general public, as we think about how to take care of our planet. Otherwise we'll continue to make decisions that adversely affect fungal communities purely because we don't know any better.

The urgency is in raising awareness and in the study of methods for conservation of fungi. Trying to figure out what actually works for protecting these organisms, so that we can move into the implementation phase. We need to figure out how to turn conservation of all life on earth into integrated policy, economic systems, and livelihoods.

Fungal resources in Kenya

Recently I have begun to think about how to build systems that connect people and nature in Kenya, where I'm from. I'm interested in systems that will allow for sustainable development of the country, while preserving both cultural heritage and natural environment. Many things have been tried in the past. I would like to see communities get behind the science, and the intention to bring science into the general public, discussing how it integrates with policy and economics.

My exploration in the work and part of my thinking is anchored in considering Kenya's rapidly degrading grasslands or mangrove ecosystems. These are resources which many communities heavily rely on. I'm beginning to see mycorrhizal fungi as a way to underpin new ways of development and connection in my home country. How can we change our focus from managing pastoralism and wood cutting in mangroves? How can we change our focus to protect underground communities and get the edge that we need to make a difference and start restoring ecosystems, taking care of our communities, building economic independence, and decolonizing our economy. I am realizing that fungi have a magical way of making you think like that–that you can go against the grain and be rebellious.